24 Nov From the World Society – On Sustaining Our Cultural Organism

We are a cultural organism.

We can marvel at the challenge that Rudolf Steiner gives to us during the Christmas Conference, for it is here that he creates an imagination of how to carry and sustain anthroposophical life in a way that had not been previously possible. He did not suggest the familiar forms of institutions or organizations, but moulded and shaped a vessel that would be a living, growing, ever evolving organism.

This new vessel for a being had its challenges from the outset for its members, unfamiliar with such an entity, expected it to conform to predictable structures, familiar forms. This challenge remains for wherever anthroposophy seeks to reveal herself, the world demands that we establish familiar ways of working to give it legitimacy. Our challenge is that these inherited organizational frameworks confuse the task of sustaining a remarkably elaborate living organism.

We can observe the advance of winter and be struck by the complex interrelationships of the organic world within which we live. The universe of plants and animals responds with unfailing sensitivity to the waning light, to the receding warmth. Forests have dropped their leaves and animals have retreated to their shelters. All of nature responds as a unified organism. Each tree and animal, each bird and insect unfailingly takes its place within the almost inconceivable unity that we call nature. All are vital cells within the vast living system that is Natura herself. No construct, no abstract formulation, dictates their unswerving constancy to their task within the whole. Rudolf Steiner asks us to be conscious of a similar reality. He calls us to so connect ourselves with the being of anthroposophy that we begin to recognize that we long to link ourselves with life processes that sustains and strengthen her ability to become ever more present.

This runs contrary to familiar institutional structures. What we have learned is difficult to transform. The habits we have developed for how we cultivate our relationships have crystallized into institutions that bind life. We become uneasy when we cannot fix, cannot predict how life processes will manifest themselves. Rudolf Steiner asks us to be ever attentive to whether we serve such institutional forms, or life.

To see that wherever we strive out of anthroposophy is part of a universal, a cosmic reality, is extremely challenging for us. We want to see the tree rather than the forest, the bear gorging itself on berries rather than the animal kingdom preparing for winter. Yet we are challenged to see that the life within a Waldorf school in Ontario is inseparable from one in South Africa or Brazil; that the well-being of the biodynamic farmer in India has its affect on his counterpart in British Columbia. Yet more challenging is to experience that the health and vitality of what is built up in a members’ group in Halifax nourishes all Waldorf schools, strengthens all biodynamic initiatives – like oxygen circulating in our blood, like light and warmth that calls the forest awake in spring.

Each endeavour becomes a face of anthroposophy. As we begin to perceive her as a living entity Rudolf Steiner asks us to become vehicles for her intentions – to bring about a transformation of human culture. We are asked to be conscious that our efforts, our actions, support her in realizing a metamorphosis of human relationships – that we become true human beings. Though mighty in its imagination its realization is simple – built upon the alignment of our individual actions with the consciousness of this totality, of this living reality.

For some our ability to devote ourselves to this cultivation of a new cultural organism is limited. Others devote their lives to one aspect or another of this complex being. We devote ourselves to the practice of an anthroposophical medicine, the practice of an anthroposophical education, the practice of an anthroposophical art. Each one an aspect of the whole.

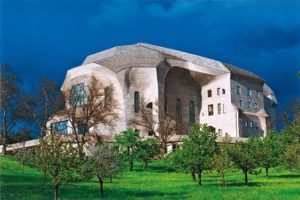

But there are also a few who we have asked to dedicate their lives to supporting and nourishing the being as a whole. This small group of ‘cultivators of the whole’ have over the past century lived and carried out this task at the Goetheanum. They have turned their volition from their individual aspirations and committed themselves to us, each one of us carrying our individual impulses wherever we are in the world. This ‘cultivation of the whole’ has asked much of these individuals – to set aside what they would want to do out of themselves and to redirect their initiative toward this difficult all encompassing task. In so doing they make themselves truly vulnerable. They are asked to leave behind their networks of family and friends, and to carry all of us as a new and vastly extended set of relations. They have also had to place their well-being in our hands, to rely completely upon our support for them in the challenging task of nurturing and sustaining the whole out of the complex manifestations of the countless parts.

We enter into a completely new condition when we all carry this consciousness together. This being of anthroposophy is only able to be sustained when we agree to trust each other in this immense task. Trust is not an unquestioning acceptance. It cannot exist without discernment, without care and concern for each other.

As we reflect on this, we can begin to understand why Rudolf Steiner wanted us to have an immediate, a practical relationship with this expansive reality. So it is that one of the few conditions of membership is to practice demonstrating this relationship. We do so when each financially supports those who have set aside their individual striving on behalf of us all. This seemingly simple act makes real the direct relationship between each of us, busy in our different initiatives, and those who devote themselves to holding the totality of being.

It takes a shift of consciousness by each of us to bring about the realization of the living organism that makes possible the transformation of our cultural life. By acknowledging this in the most practical way possible, acknowledging that we must sustain those who would ‘carry the whole’ brings the ideal into action.

As members of this great organism in Canada we have cultivated, perhaps unconsciously, a sensitive understanding of these complex interrelationships and of our interdependence upon each other. We have come to recognize that there are some among us who cannot fully meet their part in sustaining those at the Goetheanum. What this has meant is that others of us have supported our fellow Canadian members, contributing for those who cannot do so themselves. When we consider the whole picture, it is heartening to be aware, and important to acknowledge that almost half of our fellow Canadian members recognize these complex interrelationships and contribute more than what is asked of them – in some cases significantly more. This is a remarkable gift. We can all be grateful for this generosity, recognizing that it both supports those in our own groups with financial limitations while simultaneously assuring those needing our support have their needs met.

As we go into a new year, perhaps we can become ever more aware of this great task that destiny has brought to us – that it asks many things of us. It is easy to lose sight of the scope of the mighty presence of anthroposophy, and that she is truly vulnerable, completely dependent upon what each and every one of us does. It is only our deeds that make it possible for her to be sustained.

With warm regards,